From conversations we’re having with financial advisers, it seems that many of their clients are asking the same question: “With equity markets looking so stretched, should I be investing in property instead?” Our answer: tread very carefully.

The old adage “safe as houses” has a universal appeal but often seems particularly meaningful to investors when, as now, financial markets look fully priced. Quite simply, bricks and mortar appear to be more secure.

But why should investors take this view when—as history suggests—housing can be riskier than many people expect?

We believe the answer lies in the power of myth, and in Australia there are three myths about the property market that seem to persist in the minds of many investors. They are: “the property market never goes down”, “it will never go down in my city” and “property is always safer than equities.”

The danger of these myths is that they can blind investors to some important realities about the property market, and prevent them from thinking in broader and more effective ways about how to manage risk and return across their portfolios.

We’re not saying “don’t invest in property”; we are saying, however, that the myths about property don’t stand up to hard analysis, and that investors should understand the risks of the asset class and manage their exposures to it appropriately.

MYTHS BUSTED

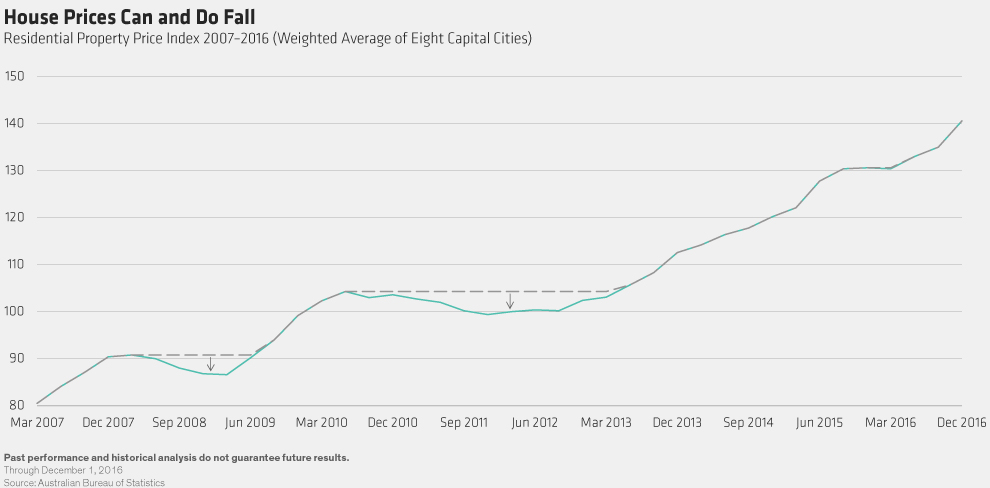

As the display below shows, house prices can and do fall, and have done significantly on two occasions across Australia’s capital cities since 2007.

Over time they’ve recovered and resumed their upward trajectory. Owner-occupiers may take such setbacks in their stride, if they think of their homes as long-term assets and are not too worried about short- and medium-term price movements. For investors who look at property as an alternative to equities, however, it should be a sign that there’s more to this “safe” asset class than meets the eye.

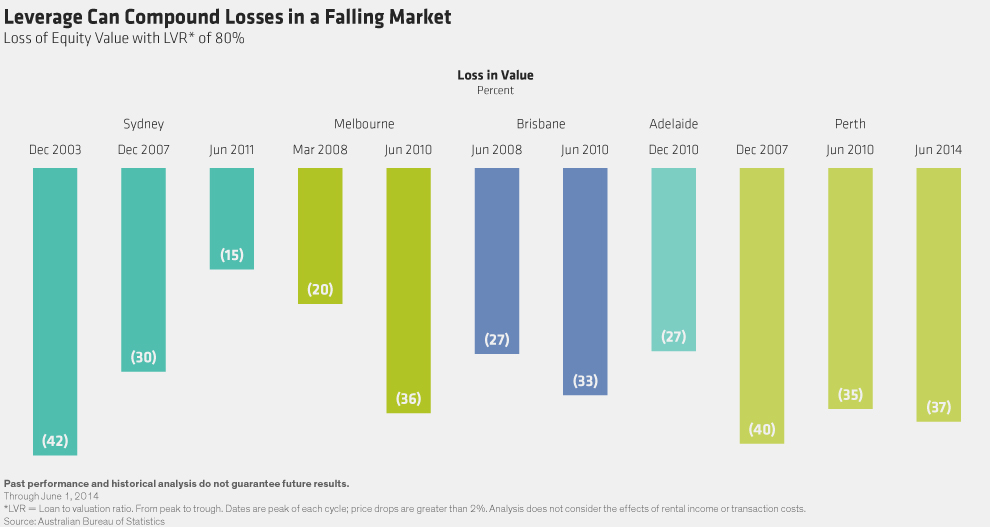

As for the idea that the property market will never fall in “my” city, the next display provides a sobering corrective. House prices fell on average by around 9% across all capital cities after the 2008 and 2010 peaks. For the five major capitals, the average fall was more than 10%. The outlier, Perth, experienced a fall of around 15% after the 2013–2014 peak.

Even these fluctuations may seem more benign to some investors than the extremes of volatility occasionally experienced in the equities market. When comparing property and equities, however, it’s important to bear in mind a key differentiator between the two asset classes: the use of leverage.

WHEN GOOD DEBT TURNS BAD

The practice of borrowing money to invest is more widespread in the property market than in the equities market. This has significant consequences in the property market because it means that just as leverage can compound gains when the market goes up, it can also compound losses when the market falls.

Take the example of an owner of a house worth $1 million bought with an $800,000 mortgage. A $100,000, or 10% fall in the value of the property (the same as the average percentage fall in house prices across Australia’s capital cities in 2008 and 2010) may not seem too bad at first sight, but it represents a 50% fall in the owner’s equity, from $200,000 to $100,000.

In practice, the losses can be even steeper, as the next display shows.

The extent of the damage depends on the loan-to-valuation ratio (LVR) and how far prices fall. After the 2010 peak in Sydney, for example, borrowers with a 70% LVR saw their equity fall by 10%, while those with a 90% LVR suffered a 30% loss. The comparable losses in the more traumatic downturn of 2003 were much worse—nearly 30% and 85% respectively. Similar patterns can be seen across other state capitals.

CLARIFY AND DIVERSIFY

What should investors do? They should go back to first principles, in our view, and ask themselves: What am I trying to achieve? If the answer is “reduce potential volatility in my portfolio without sacrificing too much long-term growth”, there are other solutions available to them.

They might consider, for example, diversifying their equity allocations with a low-volatility strategy—one which ideally focuses on mitigating downside risk without the use of market benchmarks, derivatives, shorting or leverage.

We’re not saying that such a strategy should be an alternative to any property exposure, but it could potentially offset volatility in a portfolio’s property and conventional asset-allocations while also contributing to the goal of achieving long-term growth.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.