15 min

The resurgence of COVID-19 in parts of Australia has strengthened the likelihood that the pandemic will remain a key policy concern for some time. As well as being a risk, it is however acting as a catalyst for deep-seated risks that were present before the pandemic began.

From the start of the COVID-19 pandemic it’s been apparent that, in the absence of a vaccine or a breakthrough in the treatment regime, the virus will remain a key policy concern and will have a material impact on the economic outlook. The challenge has been to understand how the policy implications are likely to evolve, and how the risks posed by the pandemic might intersect with those already facing local and global economies and financial markets.

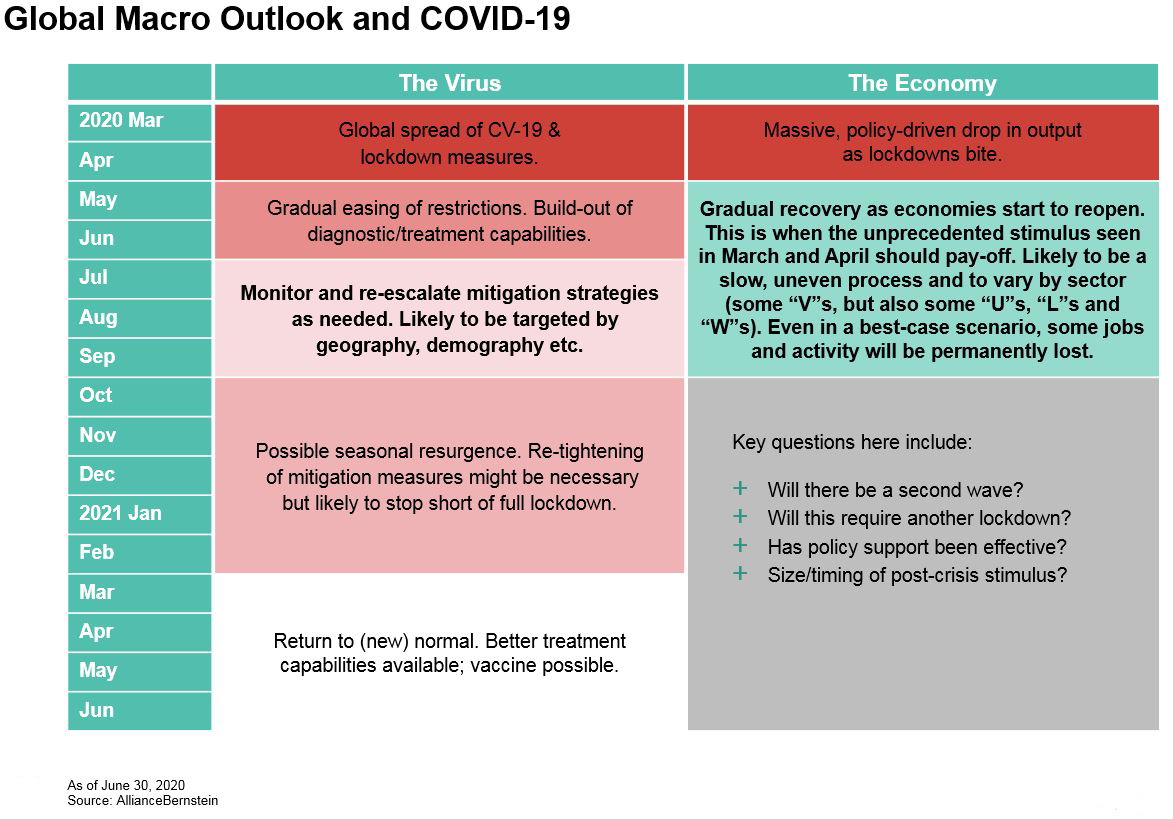

One way to think about this is to consider how the pandemic might run its course, its likely impact on the economy and probable public health and policy responses. To that end, we’ve sketched out a road map for the next year or so (Display):

Most countries went through the sharp contractions shown for March and April as various restrictions were implemented. In many countries—outside the US and most emerging markets—those restrictions helped to bring the virus back under control. And, as restrictions have eased and economies have re-opened, activity has started to recover.

As we’re now seeing in Australia and especially Victoria, however, managing the pandemic appears to require continuous effort on the part of government and the public, and it may not get any easier with time. Indeed, it may become more difficult if the initial sense of we’re-all-in-this-together solidarity begins to wane and the public starts thinking about the pandemic as just one of the many other challenges it must deal with every day.

Even before this “two steps forward, one step back” setback occurred, we were very wary about extrapolating the “V”-shaped-recovery of May and June into the second half of the year. This was because we are yet to experience the longer-term headwinds that the pandemic has created.

Difficult outlook for the unemployed

We’ve already seen a big change in consumer spending caused by restrictions: two obvious casualties are international travel and large public gatherings. These sectors are likely to remain under pressure for as long as restrictions last, which could be a while. Occupational health-and-safety requirements will mean that some businesses will have to rethink how they restructure their workplaces, whether they are in open-plan offices or more specialised environments, such as abattoirs.

Certain behavioural changes may also be permanent. Many businesses, for example, will have to consider the fact that some of their employees have discovered they can work effectively from home, and want to continue doing so, part- or full-time, and perhaps permanently.

While disruptions are by no means unusual in business, this disruption is large and broadly-based. It might lead to efficiencies and savings, but it could also lead in some sectors to reduced investment and stagnation. We expect the recovery to follow a path in which output will be well below what it would otherwise have been if COVID-19 had not happened, and that means some difficult times ahead for the unemployed.

These disruptions have been caused not just by lockdowns and other restrictions but by the fear factor, and the fear factor is likely to persist for as long as takes to develop a vaccine or at least a very effective treatment regime. While this affects the composition of consumer spending it may also have an aggregate impact—driving up, for example, the desire to save.

A catalyst for other risks

One of the highest convictions we have about the outlook is that the pandemic is, in a sense, pushing at an open door. Whether it’s de-globalisation, the rise of populism or the debate about how governments need to manage the rising tide of public debt—the pandemic is exacerbating all these issues and making them more urgent.

The management of public debt is critical. If you think about the options that governments have, they can restructure the debt, which is not a palatable course of action for most countries, or they can make it more manageable by increasing the size of the economic cake—that is, as a result of economic growth. Even before the pandemic, this option faced challenges because of ageing demographics, de-globalisation and low productivity, and it’s even more problematic now. Austerity is another option but, as recent experience in Europe has shown, this tends to be self-defeating.

This leaves financial oppression as the only option, and we’re seeing that to some extent in central banks being under pressure to keep interest-rate structures low, and in the move to modern monetary theory and fiscal policy dominating monetary policy. Normally this would cause concern of a return, at some point down the track, to higher inflation. In the very short term, of course, concerns about inflation will take a back seat, and the extraordinary policy settings we have, at least on the monetary side, will continue for an extended period.

This is how we tend to think of the pandemic’s impact—not so much as a stand-alone risk but as a catalyst for many others. It’s already contributed to rising geopolitical tensions between China and other countries (through calls for an inquiry into the cause and management of the pandemic) and may affect some aspects of this year’s US presidential election campaign. Once we see our way through the short- and medium-term effects of the pandemic, there are plenty of other issues to worry about.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams and are subject to revision over time.